Berthon UK

(Lymington, Hampshire - UK)

Sue Grant

sue.grant@berthon.co.uk

0044 (0)1590 679 222

Berthon Scandinavia

(Henån, Sweden)

Magnus Kullberg

magnus.kullberg@berthonscandinavia.se

0046 304 694 000

Berthon Spain

(Palma de Mallorca, Spain)

Simon Turner

simon.turner@berthoninternational.com

0034 639 701 234

Berthon USA

(Rhode Island, USA)

Jennifer Stewart

jennifer.stewart@berthonusa.com

001 401 846 8404

October 13th, 2025

by Peter Burt

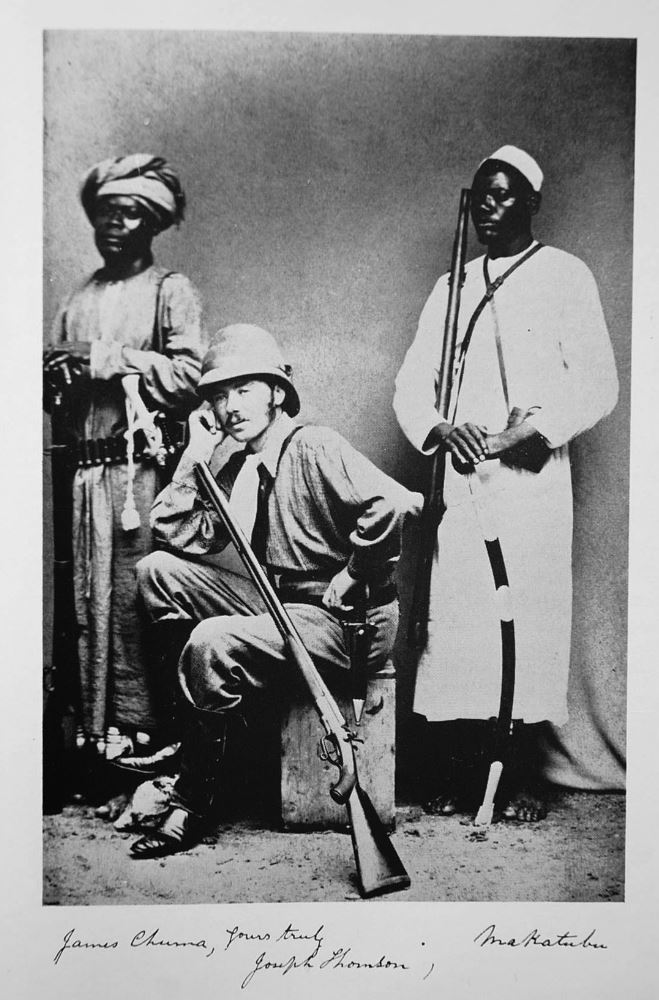

^ Joseph Thomson and James Chuma | Photo courtesy of the RGS

Collectors and their collections come in many different forms. I’m a watch collector. Although I happen to wear a Rolex submariner, probably the most robust and best of that breed, it is a working watch, not part of my collection.

I started collecting pocket watches as a child after playing with a wonderful, gold, Hunter cased, Victorian Chronograph, sailing watch. A fine piece of the watch maker’s art and a handsome and useful tool for any racing sailor. I remember it like yesterday and at the age of five it made a huge impact on my life and led to many adventures and to making quite a few friends. Step forward nearly sixty years and in my wanderings, I was offered an extraordinary pocket watch. I have collected naval and private ‘Deck’ watches, (navigating watches) in their handsome: mostly mahogany boxes, for many years but this was different.

This silver cased, open faced watch was a large, heavy, tough watch with a screw-on flat glass and a screw-on back with a tiny chain securing a screw-on cap over the winding crown. In fact, a truly waterproof watch, created and used 50 years before The Rolex patent waterproof watch of the mid-1920s. It was inscribed on its plain, silver back: Royal Geographical Society. No. 28.

I was immediately intrigued. My father had been a fellow of the RGS from the early 1930s. I bought the watch, and it has led me through many years of research on probably the rarest, best recorded and catalogued, group of watches in the world.

These are the so called RGS Explorers’ watches. They were lent to members and Fellows of the Society between 1878 and 1939.

These 138 ‘Travellers’ (they were never called Explorers, much too vulgar), were the great British explorers of their age. In fact, the only outstanding man who didn’t carry these watches was Robert Falcon Scott, who was supplied by the Royal Navy with Smiths watches, to RGS pattern, one of which can be seen at the Greenwich Maritime Museum.

Ernest Shackleton borrowed 4 for his first great adventure into the Antarctic in 1907. The list of Travellers reads like a list of almost all the men who ventured across the world, driven by the bug of escapism, discovery and adventure.

^ RGS No. 5. | © Photos courtesy of David Penney

Take RGS No. 5. Supplied to the East African Expedition and finally to Joseph Thomson in 1878, as second in command of the Society’s East African Expedition, exploring the possibility of creating a new road from the east coast of Africa near Dar es Salaam, to the Great Lakes of Victoria and Tanganyika over 500 miles away, as the crow flies. The leader of the expedition died of fever, 5 weeks and only 145 miles into the centre of an unknown area. At the age of just 20, this bright young Scottish lad had to decide whether to carry on or go back. He went on, walking the nearly 3,000 miles with his 128 men. He was captured and released twice, faced attack and talked his way out of trouble, and was the first European to walk between the Lakes of Victoria and Tanganyika, eventually returning to the coast through what were thought to be the hostile lands of the Maasai and although he suffered from fever for some of the time, he kept walking. 14 months later, he reappeared at the coast, having never lost a man from his huge team or injured anyone they encountered. He returned to England a hero and became an explorer of other parts of Africa. The great herds of Gazelle in Southern Africa were named after him, Thomson’s gazelle.

My next traveller was Harrison, who, after losing his father decided he too would go to the wilds of upper Canada and survey the Mackenzie River Basin. He walked the equivalent of London to Sicily and back, surveying part of the 690,000 square miles of the Basin, in the course of 3 summers and 2 winters. The lowest temperature on his travels was minus 67 degrees Fahrenheit. He lost RGS No. 28 for 7 months and made a 200 mile walk to successfully find it in the early summer of 1907.

There were 26 watches purchased by the Society. The Instrument Book numbers them, records the name of the maker and supplier, the date of purchase, the actual number of the watch movement, and sometimes the reason for purchase. The second Instrument Book records the lend and return of every watch and here we find wonderful, acerbic comments in a cramped hand on who borrowed which watch, where it was going to be used, where it actually went, comments on its condition when returned (or not) and when it was sent to be repaired or rebuilt.

11 watches were irretrievably lost. Some of the notes read:

“Dear Secretary, I regret I am unable to return the Society’s watch as I had to trade it for the return of my wife”

“The watch you lent me was stolen by natives on the train, on the way to Khartoum”

“Returned by his assistant as Mr. Becher drowned on the 3rd day of the expedition”

“Colonel Fawcett and his son walked, with their supporters into the jungle and were never seen again”

These watches were always expensive, In 1878 they cost £35, (about £3,000 now). They are remarkably resilient and reliable watches known as half Chronometers. When looked after carefully and wound every day at the same time, they could be successfully used for keeping GMT anywhere in the world from high to low latitudes and in hot or cold climates. They were generally used singly or in threes. In my research and in looking at website, going to the great sale rooms both in the UK and the USA and talking to many dealers, I have only found five and the possibility of a sixth. I have advertised to see if I could identify any other real ones but have not found them. The five I have seen are now all cased in beautiful mahogany Victorian style deck-watch boxes, which gives them some safety and an extra charm.

^ Bagnold 1930 taking a compass bearing in the Desert | Photo courtesy of Stephen Bagnold

There have been fakes created, but they are easily dismissed. They may be real explorers watches which have later been engraved with false RGS names or numbers. I hold copies of all the Instrument Books and occasionally I am asked to confirm or dismiss RGS watches that have been found. As a Fellow of the RGS, the Society sometimes sends me queries about these watches they have received, and I am still studying and reading at the Society’s wonderful Library in Exhibition Road, London.

There are quite a few Explorer’s watches to a similar pattern that come on the market. The few I have seen were made by Smiths, Dent, Ogden of London, Lund and Blockley and others. The rest of the RGS watches remain unseen and incredibly rare and change hands amongst dealers and collectors for increasing sums of money, each watch often having an amazing history of adventures in countries all over the world.

The final watch I will mention is No. 21. Borrowed from the RGS and used by Major Bagnold of the Royal Engineers, in 1930 for navigating a private expedition in specially designed cars, across the Libyan Desert. Bagnold, a great polymath, (inventor of the Bagnold sun compass, author of many books, advisor to NASA on the possible surface of Mars) and his team learnt how to drive up into the sand dunes and along their tops covering long distances exploring where only camels might have trodden before. Their 3,000 mile journey was a huge success and obviously great fun, though sometimes very hard work. Ten years later, known as an expert on the sands of the eastern Sahara, Bagnold, who was passing through Cairo in 1940, was asked to form a new group for the British Army. At General Wavell’s request, he created and commanded the Long Range Desert Group who, with much panache became hit-and-run pirates of the great sand sea, destroying Italian and later Nazi fuel dumps, camps and aerodromes and from which later sprang the SAS.

^ RGS No. 21. | © Photos courtesy of David Penney

These handsome, chunky, RGS watches are amazingly rare and have become much sort-after for the stories in which they have been involved. Each watch is a piece of real history and a great conversation object for connoisseurs at the dinner table, fi ne pieces of history to carry in a pocket and produce to show friends. Whilst they have given me a fascinating chance to learn about people and the world they have also kept me away from sailing on the odd sunny day.

The problem is finding any watches of the 15 that might still be out there. Do you know of another?

Read Another Article

Download The Berthon Book 2025-2026 XXI (22.1MB)